Authored by Richard Howell

What exactly is Yin-Yang? Its symbolic representation is common enough but it would be a reasonable bet that few who observe it will know much about its meaning, beyond thinking that it has something to do with opposites or duality.

What exactly is Yin-Yang? Its symbolic representation is common enough but it would be a reasonable bet that few who observe it will know much about its meaning, beyond thinking that it has something to do with opposites or duality.

One approach to a truer meaning, is to consider what it is not. It is neither a force nor an energy. You cannot see it, feel it, breath it or hear it. It has no physical presence but as the Chinese might say, it exists.

It is in essence a philosophical concept, a means by which one can reach an understanding as to the nature of existence without having recourse to science or theoretical physics.

To think of Yin and Yang in terms of opposites is misleading. To term one thing as opposite to another is to imply that they are fixed and unchanging but the idea that anything can be so situated is contrary to what is implied by the segments within the circle.

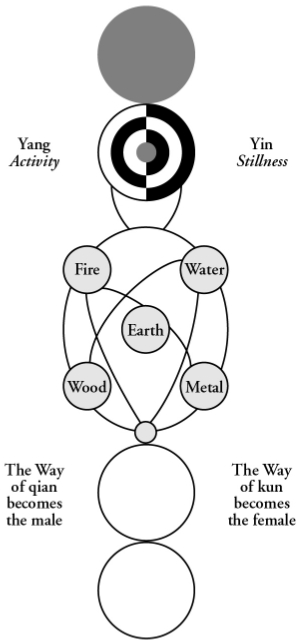

What it depicts is the totality of existence (the outer circle—tai chi, the grand ultimate in Taoist thinking) inside which all things at all times are in a constant state of increase (Yin—the dark segment, to Yang—the light segment) followed by decrease (Yang to Yin). The small circles at the centre of each segment represent the ever present potential for change, that which increases will ultimately decrease and visa-versa. There are no absolutes and therefore there can be no opposites—only maximum and minimum potentials.

Historical Background

The origins of Yin and Yang are (so far) unknown. One could speculate that they came about through observations of a changing natural environment but in reality only two things are certain—one, that the origins lie a long way back in time, and two, its impact was significant enough for it to form the foundation stone of classical Chinese science, religion, philosophy and medicine.

The origins of Yin and Yang are (so far) unknown. One could speculate that they came about through observations of a changing natural environment but in reality only two things are certain—one, that the origins lie a long way back in time, and two, its impact was significant enough for it to form the foundation stone of classical Chinese science, religion, philosophy and medicine.

It is interesting to note, if only for academic reasons, that while the concept of yin-yang dates back to China’s ancient history, the present taijitu diagram as shown above is no more than a few hundred years old (if that). Other versions predate it, for instance that of Zhou Dun-yi (1017–1073) (shown left) and that of La Zhide (1525–1604). More intriguing perhaps is that other ancient cultures have used emblems that resemble the taijitu, in particular the Romans, who used it on their shields (shown above right) as far back as the 3rd century CE.

What then has yin-yang theory got to do with martial arts and in particular, Taijiquan?

Chinese martial arts have been practised for many centuries. The earliest references can be found in the Spring and Autumn Annals which dates back to at least 500 BCE.(1) Since then, fighting forms have been changed and modified, largely as a result of changes and developments in Chinese society.

In the late 17th century CE the concept of internal and external styles was introduced, or at least, that was when it was first mentioned in writing.(2) External (waijia) was applied to any style that focused on physical strength, speed and agility. It was often associated with Buddhism as many of these styles originated in Buddhist temples. Internal (neijia) applied to any style that focused on spirit, the mind, the manipulation of chi (qi) and achieving results by harnessing an opponents’ force rather than fighting against it. Its philosophical foundation is/was or has become, Taoism.

This broad classification of styles can be confusing as they all have aspects which are internal and external but it does help when considering Yin-Yang theory and the part it plays in Taijiquan, the most prominent and well known of all styles classed as internal.

Taijiquan’s history is a subject that is much debated and disputed, particularly within China. Reliable historical records are, to say the least, scarce and its link with Taoism may well be a much later development than some commentators suggest. That is, no earlier than the beginnings of the 19th Century. Taoism however is most definitely much older than Taijiquan.

Originally inspired by the Taodejing(3) (late 4th to 3rd century BCE) Taoism gradually developed to become one of three prominent philosophies to hold sway over China’s emperors and people alike. While it embraced many aspects of Chinese folk religion, its primary focus was on nature, wu-wei (action through non-action) and living life according to The Way.

During the Warring States period the theories of the School of Naturalists, which synthesized the concepts of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, were incorporated into Taoist thinking and became its cosmological foundation. Written in the same historical period, the Taoist classic Zhuangzi introduced the concept of Taiji (grand ultimate—among various interpretations) which has become symbolically represented in the Taijitu (Figure 1). Taiji can be described as follows:

Tao is the first-cause of the universe. It regulates natural processes and nourishes balance. It embodies the harmony of opposites—Yin and Yang. The interaction of Yin and Yang, ever changing, ever evolving one into the other, produces chi the power which envelopes, surrounds and flows through all things, living and non-living. It is the duty of all individuals to follow a path which leads towards the Tao and become one with it.(4)

In Taoist thinking, existence is brought about and maintained by chi, and that being one with the Tao can be achieved by harmonizing Yin and Yang. Therefore an individual’s actions can be helpful or harmful to the flow of chi. If chi is the very substance of life then it makes sense to act in ways that improve its effects, both to the one’s body and the environment. If it is indeed true(5) that Taoist devotees practiced Dao Yin (an internal style exercise to promote good health) as far back as the Warring States period then it is not too difficult to see where the development of internal style martial arts sprang from.

As a concluding note, it is important to remember that the term ‘Taijiquan’ (or ‘Tai Chi Chuan’) and Taiji (or Tai Chi) have distinct meanings. Taiji (Tai Chi) means ‘grand ultimate’ and is a philosophy, Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan) means ‘grand ultimate fist‘ and is a martial art.

Before the mid 1800’s Taijiquan had no defining name, it was only after the scholar Ong Tong witnessed a performance of Yang Luchan’s martial art and declared that it was the physical manifestation of the Taiji philosophy that it became known as Taijiquan. Somehow, over time and mainly in Western countries it seems, the name has been shortened to Tai Chi. That maybe one reason amongst many why so many people who practice it do not know that it is a martial art.

Forward to Part 2 – Yin-Yang in Taijiquan practice

Forward to Part 3 – Yin-Yang in Taijiquan applications

References:

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_martial_arts

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Styles_of_Chinese_martial_arts#section_2

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taoism

4. https://www.jungtao.edu/school (page no longer available)